An X1800XT in FireGL Suit? Can it play games?

- RRP: £730

- Release date: October 2005

- Purchased in October 2025

- Purchase Price: £5.60 Delivered

X1800XT cards seem to have all but vanished from eBay at the moment. In the “sold and completed” listings I could only find a single one – and someone who wasn’t me walked away with an absolute bargain at £20. The few international listings still floating around are closer to £200, which is… optimistic, to put it politely.

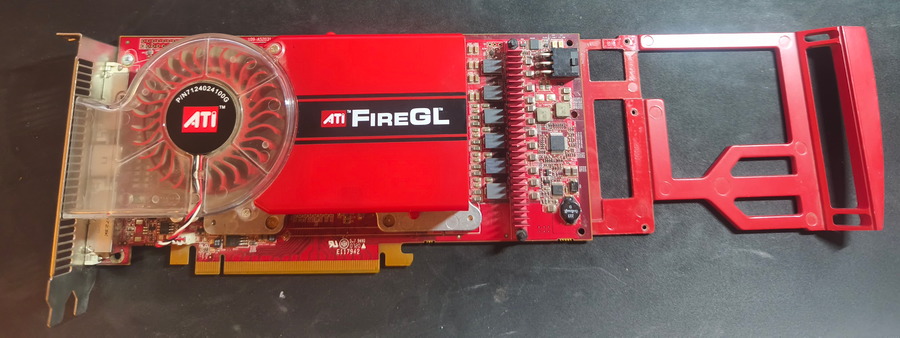

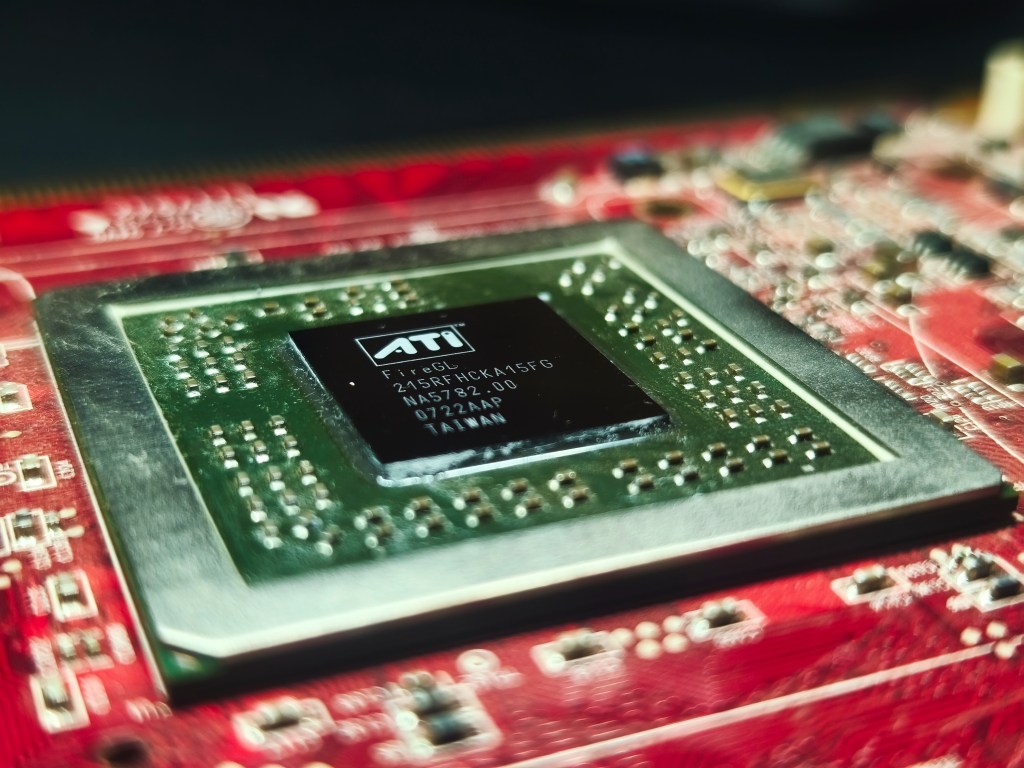

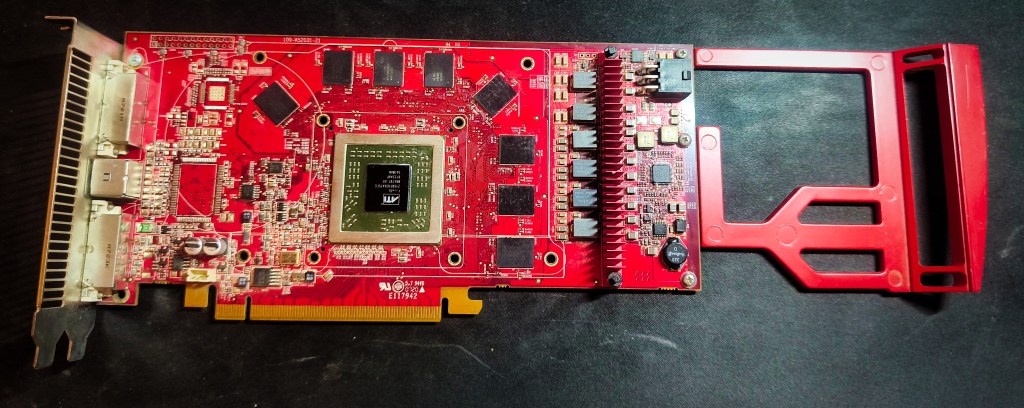

So finding this FireGL V7200, based on the exact same hardware, felt like striking gold. It looks fantastic, it’s built like a tank, and under the workstation branding it’s still very much an X1800XT at heart.

It was one of those auctions listed as “untested”, normally a giant red flag, especially when the seller deals in other tech. But in this case it was a lone graphics card among a sea of unrelated items, which made me curious. I reached out and asked for the story behind it. Turns out he’d just had it sitting in a box for years; he was more into old Macs and had no way to test it. He dropped the price to something ridiculous and told me I owed him a box of biscuits if it worked.

Well… it fired up instantly. So I guess I’d better sort out those biscuits.

Introduction – The Ati R500 Series

The Last of the Fixed-Function Giants

In autumn 2005, ATI unveiled the R500 family, known commercially as the Radeon X1000 series.

This generation was built on a brand-new architecture fundamentally different from its predecessors, but it remained rooted in the fixed-function pipeline model that had defined PC graphics cards since the 1990s.

R500 featured dedicated vertex and pixel shader hardware, supporting Shader Model 3.0, and brought significant improvements such as 90nm manufacturing, high precision FP32 shader support, and ATI’s new “Ultra-Threaded” dispatch engine, which increased efficiency for complex shading operations.

While unified shaders were still on the horizon, the R500 series gave ATI its first competitive edge over NVIDIA’s GeForce 6 and early GeForce 7 lines, especially in DirectX 9.0c and high dynamic range rendering tasks.

Notably, the technology and experience ATI gained with R500 contributed directly to their groundbreaking work on unified shaders for the Xbox 360’s Xenos GPU, which would later influence the design philosophies of the next generation of graphics cards.

The Radeon X1000 series marked a turning point, serving as both the pinnacle of fixed-function programmability and the launchpad for ATI’s leap into unified shaders in the years that followed.

ATI vs Nvidia: The final Fixed function showdown

The ATI R500 series, launched in 2005 as the Radeon X1000 lineup, competed directly with Nvidia’s GeForce 7 series—mainly the G70-based GeForce 7800 GTX and 7800 GT cards.

Architecturally, R500 introduced Shader Model 3.0 support, a 90nm manufacturing process, and ATI’s Ultra-Threaded dispatch engine, optimizing the use of its dedicated vertex and pixel shader hardware.

By contrast, Nvidia’s GeForce 7 series also used dedicated pipelines, featuring 24 pixel and 8 vertex shader units on top models, and implemented the CineFX 4.0 engine, boosting efficiency for lighting and shading effects as well as high-dynamic-range rendering.

Both lineups supported DirectX 9.0c, but while ATI invested in more efficient scheduling and precision FP32 execution, Nvidia’s design focused on maximizing pixel throughput and raw fill rates, often leading their cards to dominate benchmark scores in shader-heavy titles of the time.

Ati FireGL vs Ati Radeon

FireGL cards like the V7200 were built on the same core architectures as their gaming‑focused Radeon counterparts, in this case, the Radeon X1800 XT, but the two product lines were shaped by very different priorities. ATI’s FireGL series was designed for professional workloads: CAD, 3D modelling, digital content creation, and long, stability‑critical rendering sessions. That meant certified drivers, strict hardware validation, and a focus on precision over raw frame rate. Radeon cards, meanwhile, chased gaming performance, visual effects, and the fast‑moving demands of the consumer market.

Back in the mid‑2000s, enthusiasts quickly noticed how similar the hardware was between the two families. Some even experimented with “softmodding” – flashing BIOSes or tweaking drivers to turn a Radeon into a pseudo‑FireGL in hopes of unlocking workstation‑class performance for a fraction of the price. ATI, of course, kept the lines separate through driver optimisation, support policies, and in some cases, professional‑grade memory.

One of those workstation‑only touches was ECC (Error‑Correcting Code) RAM, which can detect and correct single‑bit memory errors. Not every FireGL card used ECC, but when it appeared, it reinforced the card’s purpose: reliability during long, complex rendering tasks where a single corrupted pixel could ruin hours of work. For gaming, ECC offered no real benefit — but for professional users, it was a safety net.

In raw performance, FireGL cards often matched their Radeon equivalents, but the specialised OpenGL‑optimised drivers could sometimes lead to lower frame rates or quirks in DirectX‑heavy games. Titles built around DirectX 9 generally ran best on Radeon cards with Catalyst drivers, while FireGL cards shone in workstation applications and OpenGL‑based software.

R500 FireGL and Radeon Translator chart

The first chart shows the FireGL card and it’s Radeon equivalent, pretty useful stuff when hunting for a bargain.

As you can see, it’s horribly confusing… and this just has the FireGL’s of this one generation.

| Model | Radeon Equivalent (Core) | ROPs/TMUs | CRAM Options | Core Clock | Memory Clock |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FireGL V3300 | Radeon X1300 Pro (RV515) | 4 / 4 | 128MB DDR2 | 600 MHz | 400 MHz |

| FireGL V3350 | Radeon X1300 Pro (RV515) | 4 / 4 | 256MB DDR2 | 600 MHz | 400 MHz |

| FireGL V3400 | Radeon X1600 Pro (RV530) | 4 / 4 | 128MB GDDR3/DDR2 | 500 MHz | 500 MHz |

| FireGL V5200 | Radeon X1600 XT (RV530) | 4 / 4 | 256MB GDDR3/DDR2 | 600 MHz | 700 MHz |

| FireGL V7200 | Radeon X1800 XL (R520) | 16 / 16 | 256MB GDDR3 | 600 MHz | 650 MHz |

| FireGL V7300 | Radeon X1800 XT (R520) | 16 / 16 | 512MB GDDR3 | 600 MHz | 650 MHz |

| FireGL V7350 | Radeon X1800 XT (R520) | 16 / 16 | 1024MB GDDR3 | 600 MHz | 650 MHz |

Top-end Radeon R500 series (and the V7200)

It’s a busy place at the top end of the R500 line. Most sources agree this is because the R580 was pin compatible with the R520, which allowed ATI to reuse the same PCB designs across multiple cards. That made it easy for them to release a whole range of models with only small changes instead of designing new boards from scratch.

I’d love to find an affordable X1950XT with its huge number of texture units, but I can’t imagine they appear on eBay very often. When they do, they’re usually priced far higher than I’d like to pay.

The V7200 sits in a more realistic spot. It’s essentially a slightly underclocked X1800XT, putting it toward the lower end of the high‑end cards. Still powerful, still interesting, and still very much part of the same family.

| Model | Code | ROPs/TMUs | VRAM Options | Core Clock (MHz) | Memory Clock (MHz) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radeon X1800 XL | R520 | 16/16 | 256/512 MB | 500 | 500 (1000 DDR3) |

| Radeon X1800 XT | R520 | 16/16 | 256/512 MB | 625 | 750 (1500 DDR3) |

| FireGL V7200 | R520 | 16/16 | 256 MB | 600 | 650 (1300 DDR3) |

| Radeon X1800 GTO | R520 | 16/12 | 256 MB | 500 | 500 (1000 DDR3) |

| Radeon X1900 GT | R580 | 12/36 | 256 MB | 575 | 600 (1200 DDR3) |

| Radeon X1900 XT | R580 | 16/48 | 256/512 MB | 625 | 725 (1450 DDR3) |

| Radeon X1900 XTX | R580 | 16/48 | 512 MB | 650 | 775 (1550 DDR3) |

| Radeon X1950 Pro | RV570 | 12/12 | 256/512 MB | 575 | 690 (1380 DDR3) |

| Radeon X1950 XT | R580 | 16/48 | 256/512 MB | 625 | 900 (1800 DDR3) |

| Radeon X1950 XTX | R580+ | 16/48 | 512 MB | 650 | 1000 (2000 DDR3) |

Turning FireGL into Radeon

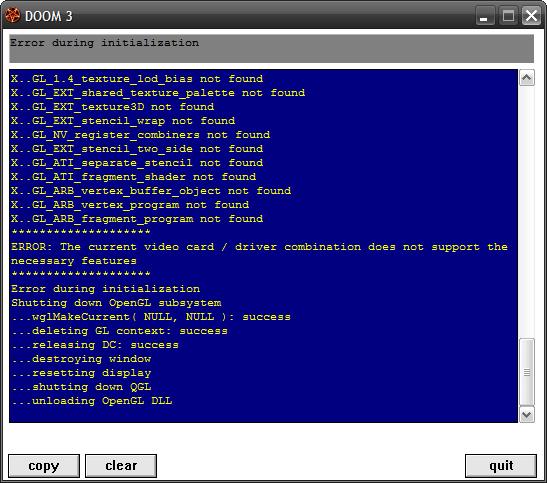

The internet is full of claims that FireGL drivers are built purely for professional workloads and aren’t optimised for games. To see whether that’s true, I needed to get the standard Radeon drivers running on my Windows XP system.

Fortunately, it’s very easy to do. Running the Catalyst installer will fail, but it still unpacks the driver files. From there, you can open Device Manager, find the video card that has no driver, and manually point it at the .inf file inside the extracted folder.

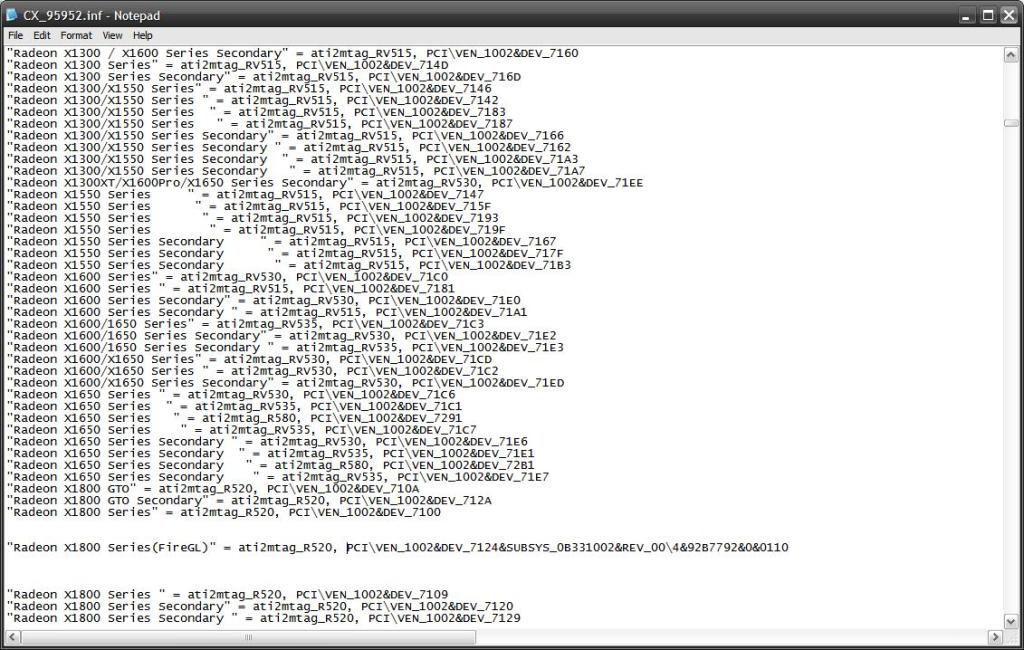

That’s the lazy method, and it was my starting point. As part of the tinkering, I also edited the .inf file to officially convince the system that the card was supported.

If you want to do the same, the first step is simply to find the device ID in Device Manager, like this:

Once you’ve copied the device ID, the next step is simple. Press Ctrl+A to highlight everything in the details window, then Ctrl+C to copy it, and paste it into Notepad so you have the exact hardware ID string handy.

With that done, open the .inf file inside the extracted Catalyst driver folder. Find the line that corresponds to the Radeon X1800. Copy that entry, change the name to something appropriate for the FireGL card, and then replace the hardware ID with the one you pulled from Device Manager.

That’s all it takes to convince Windows XP that the Radeon driver officially supports the V7200.

Once the edited .inf file is saved, Windows accepts the driver as valid for the hardware and installs it without any complaints. It only takes a few minutes to do, but is it worth the effort? Probably not. In my testing it made no difference to performance at all.

If you were feeling adventurous, another option would be to flash a retail X1800XT BIOS onto the card. It isn’t difficult, but it’s definitely higher risk than I’m comfortable with for a card I’d really like to keep alive. A BIOS flash would change voltages and the fan curve, and a bad flash could easily brick the card with no realistic chance of recovery.

The Card

Here’s GPU’z screenshot of my example:

And with the Radeon Drivers:

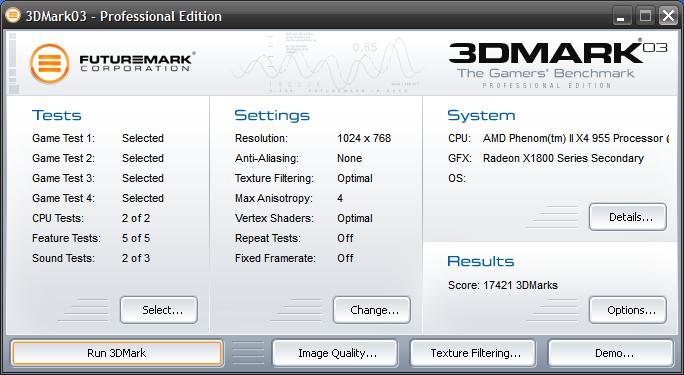

The Test System

I use the Phenom II X4 for XP testing, not the most powerful XP processor but its 3.2Ghz clock speed should be more than enough to get the most out of mid-2000s games, even if all four of its cores are unlikely to be utilised.

The full details of the test system:

- CPU: AMD Phenom II X4 955 3.2Ghz Black edition

- 8Gb of 1866Mhz DDR3 Memory (showing as 3.25Gb on 32bit Windows XP and 1600Mhz limited by the platform)

- Windows XP (build 2600, Service Pack 3)

- Kingston SATA 240Gb SSD as a primary drive, an AliExpress SATA has the Win7 installation and games on.

- ASRock 960GM-GS3 FX

- The latest WinXP supported driver version Catalyst 13.4

Onto some benchmarks!:

Return to Castle Wolfenstein (2001)

Game Overview:

Return to Castle Wolfenstein launched in November 2001, developed by Gray Matter Interactive and published by Activision.

Built on a heavily modified id Tech 3 engine, it’s a first-person shooter that blends WWII combat with occult horror, secret weapons programs, and Nazi super-soldier experiments.

The game features a linear campaign with stealth elements, fast-paced gunplay, and memorable enemy encounters.

The engine supports DirectX 8.0 and OpenGL, with advanced lighting, skeletal animation, and ragdoll physics.

The Framerate is capped at 92fps

Performance Notes:

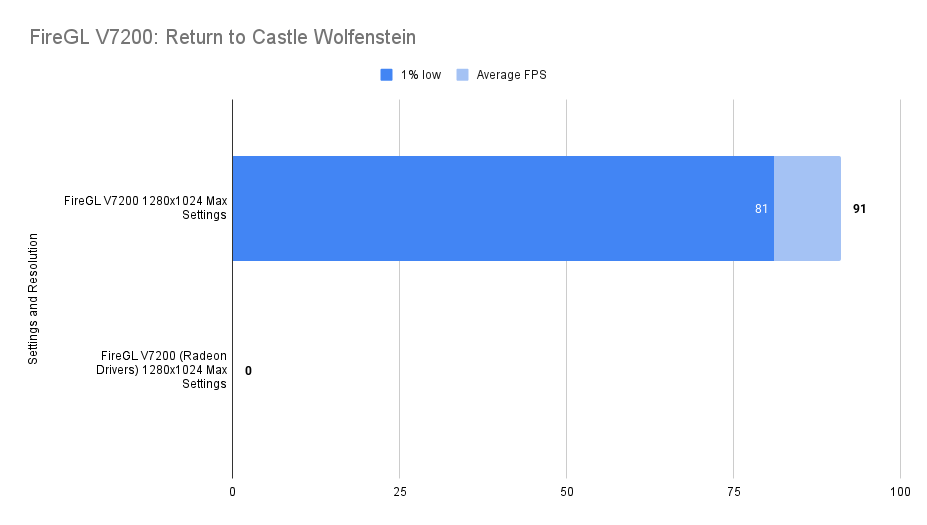

Technology moved on a lot in the four years between this game and our card being released.

As the hardware is quite end, it should be no surprise that the frame cap was hit and the 1% low was only a little lower. Clearly a smooth experience.

This would not run on the Radeon drivers however, oops, not exactly the performance comparison I was looking for!

OpenGL is apparently a problem.

Unreal Tournament 2003 (2002)

Game Overview:

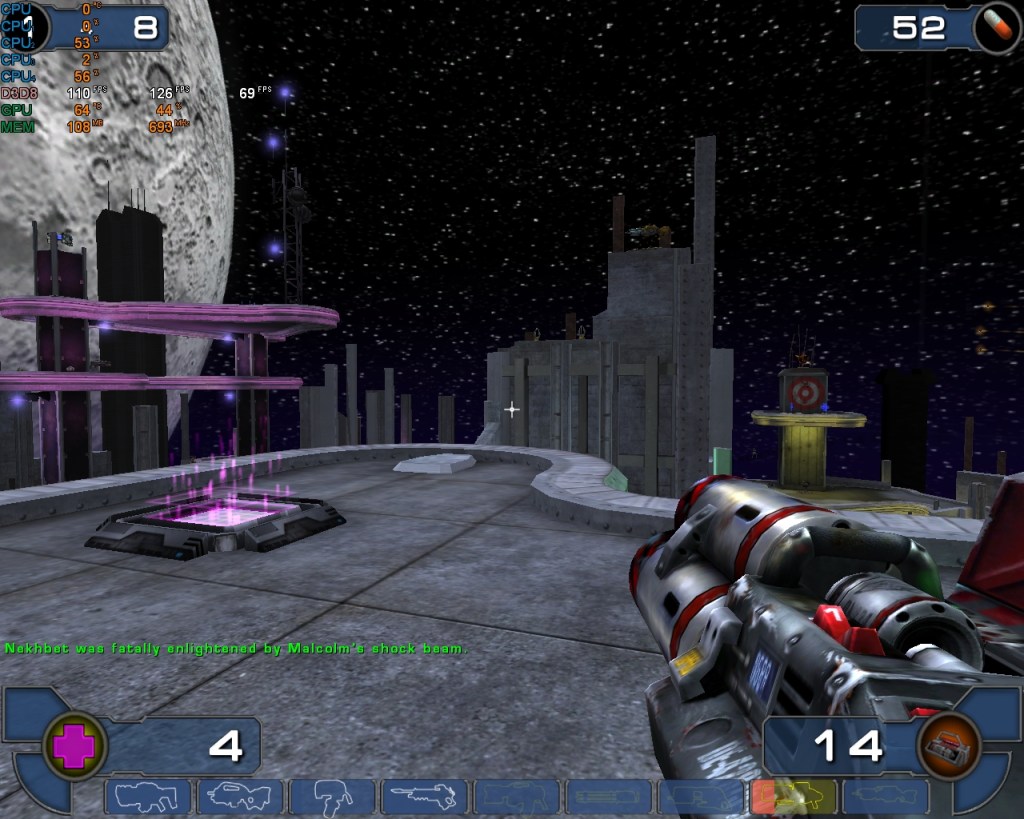

Released in October 2002, Unreal Tournament 2003 was built on the early version of Unreal Engine 2. It was a big leap forward from the original UT, with improved visuals, ragdoll physics, and faster-paced gameplay.

The engine used DirectX 8.1 and introduced support for pixel shaders, dynamic lighting, and high-res textures all of which made it a solid test title for early 2000s hardware.

Still a great game and well worth going back to, even if you’re limited to bot matches these days. There’s even a single-player campaign of sorts, though it’s really just a ladder of bot battles.

The game holds up visually and mechanically, and it’s a good one to throw into the testing suite for older cards. The uncapped frames are pretty useful (and annoyingly rare) on these old titles.

Performance Notes

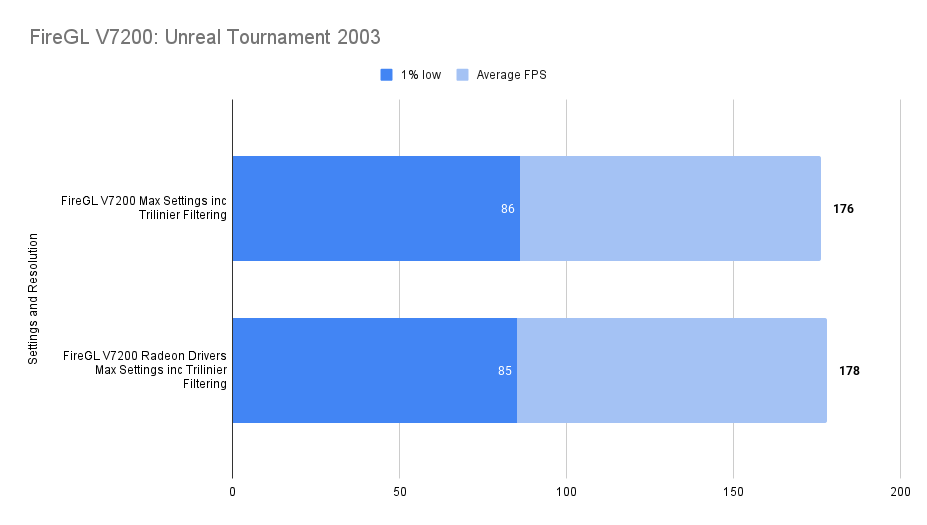

Pretty great really, a shame the consistency is not quite there.. still, who can complain when the settings are maxed out (at least on this monitor) and were hitting nearly 180 fps.

The game performs the same under both sets of drivers, easily within the margin of error.

Need for Speed Underground (2003)

Game Overview:

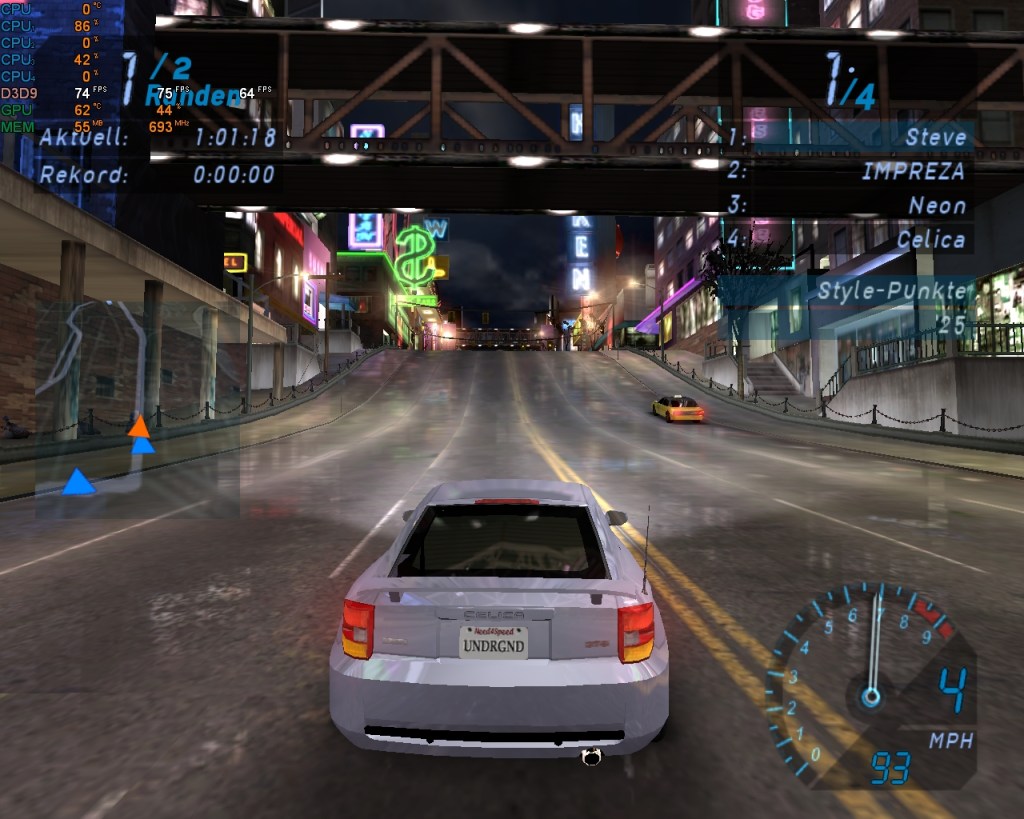

Released in November 2003, Need for Speed: Underground marked a major shift for the series, diving headfirst into tuner culture and neon-lit street racing.

Built on the EAGL engine (version 1), it introduced full car customisation, drift events, and a career mode wrapped in early-2000s flair.

The game runs on DirectX 9 but carries over some quirks from earlier engine builds.

Apparently v1.0 of this game does have uncapped frames but mine installs a later version right off the disk.

Performance Notes:

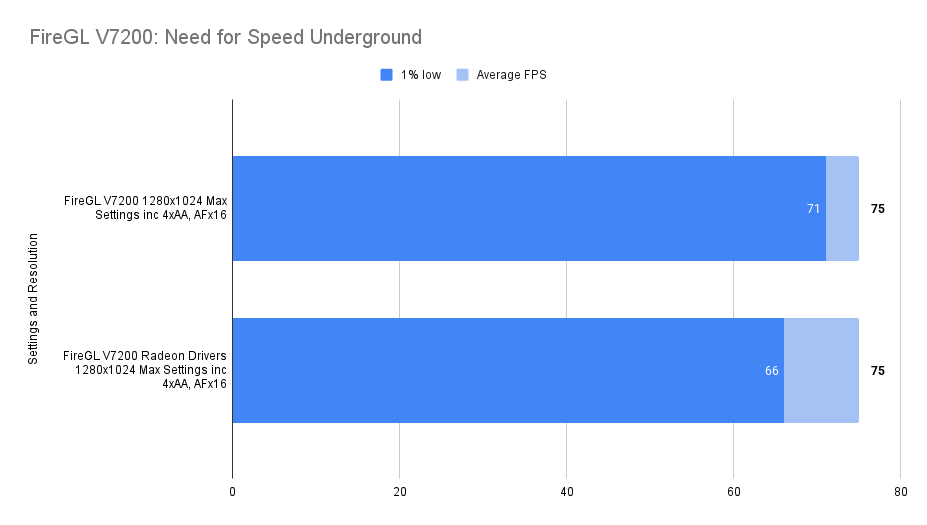

With everything maxed out, the card had no trouble hitting the monitor’s 75 fps cap and sitting there comfortably. No dips, no stutters, just a solid lock at the refresh rate.

The Radeon drivers did perform a little worse. I reran the tests and did a few extra laps to be sure, and the result was consistent. The difference wasn’t dramatic, but it was definitely there.

Even so, there’s nothing to complain about. With every setting pushed to the limit, the card still delivered a steady 75 fps, which is exactly what I was hoping for.

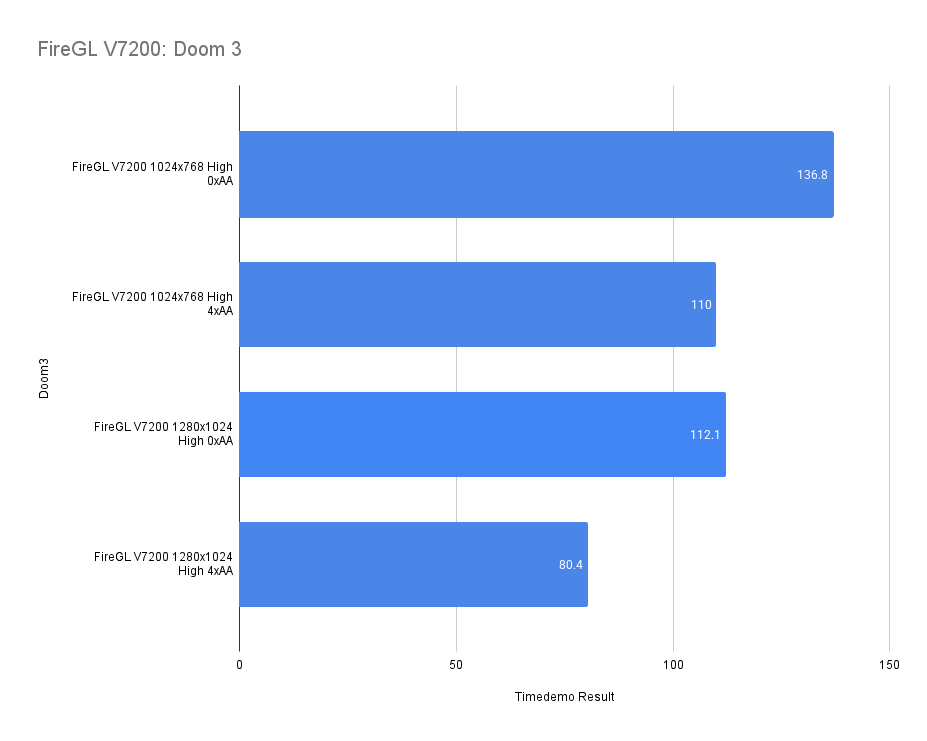

Doom 3 (2004)

Game Overview:

Released in August 2004, Doom 3 was built on id Tech 4 and took the series in a darker, slower direction. It’s more horror than run-and-gun, with tight corridors, dynamic shadows, and a heavy focus on atmosphere. The engine introduced unified lighting and per-pixel effects, which made it a demanding title for its time, and still a good one to test mid-2000s hardware.

The game engine is limited to 60 FPS, but it includes an in-game benchmark that can be used for testing that doesn’t have this limit.

Performance Notes:

Look at that framerate in Doom 3. Triple‑digit numbers across most settings, only dipping under 100 fps when running on High with 4× anti‑aliasing. For a card from 2005 wearing a workstation badge, that’s seriously impressive.

There’s a CNET article where an X1800XT 512 MB was tested, scoring 113 fps at 1024×768 and 81 fps at 1280×1024. That puts this FireGL card exactly where it should be, right in line with the retail gaming version.

You’ll also notice the complete absence of results using the Radeon drivers. That’s the OpenGL issue rearing its head again. The FireGL drivers are heavily tuned for OpenGL workloads, and Doom 3 is one of the best‑case scenarios for that optimisation. The Radeon drivers simply didn’t behave properly here, so they’re not represented in the charts.

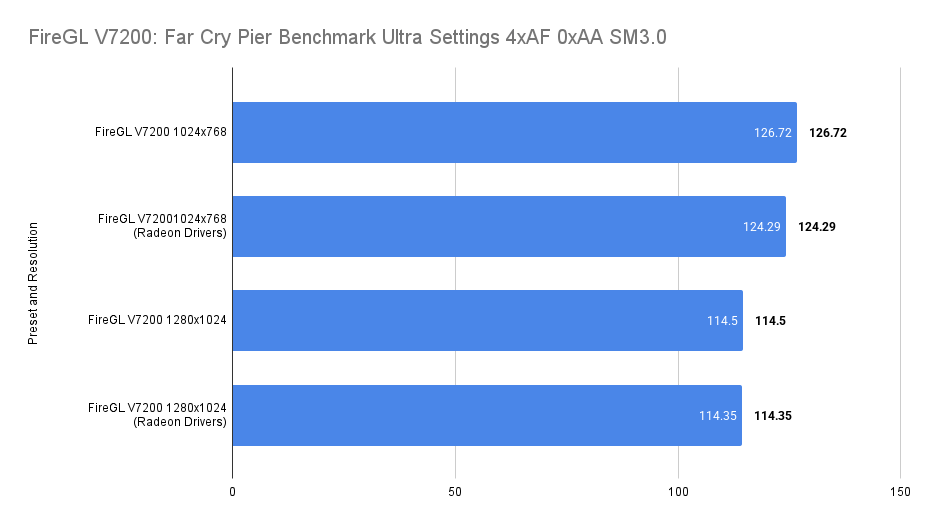

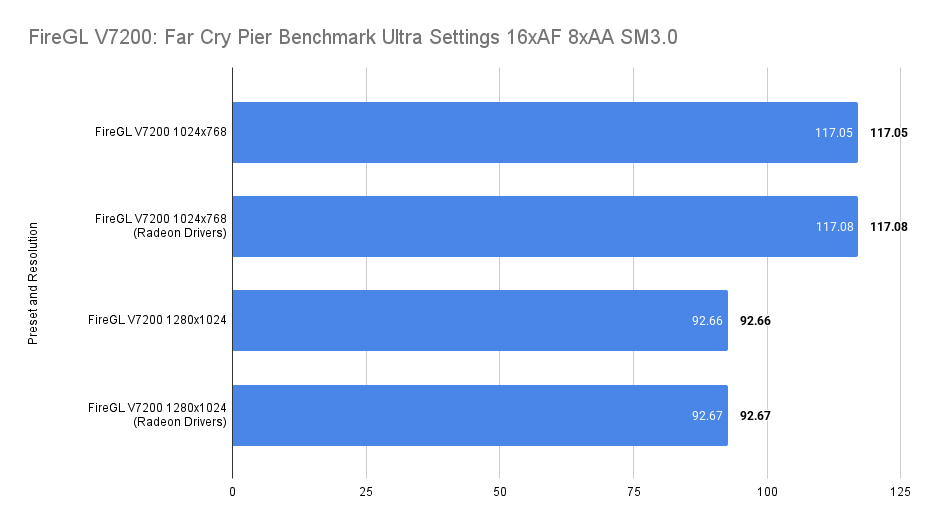

FarCry (2004)

Game Overview:

Far Cry launched in March 2004, developed by Crytek and built on the original CryEngine. It was a technical marvel at the time, with massive outdoor environments, dynamic lighting, and advanced AI. The game leaned heavily on pixel shaders and draw distance, making it a solid stress test for mid-2000s GPUs. It also laid the groundwork for what would later become the Crysis legacy.

For these tests I utilised the HardwareOC Far Cry Benchmark, this is impressive looking and free software that lets me get on with other things whilst it does three runs at chosen different settings then gives the average result with no input required.

The 1% Low figures are sadly missing but in it’s place we have some very accurate average FPS results:

Performance Notes:

The results here are excellent. Even with Ultra settings and 4× anti‑aliasing, the card stays comfortably above 100 fps. For a workstation‑branded X1800XT, that’s exactly the kind of over‑delivery I was hoping to see.

And as you can tell, forcing the Radeon drivers through was absolutely not worth the time. They produced the same numbers or, in some cases, slightly worse results. The difference is tiny, but it’s consistent enough to say the FireGL drivers are the better choice for this card.

Even after cranking things up to 8× anti‑aliasing and 16× anisotropic filtering, the card is still pushing out big frame numbers. It barely flinches. For hardware from this era, that’s seriously impressive.

F.E.A.R. (2005)

Game Overview:

F.E.A.R. (First Encounter Assault Recon) launched on October 17, 2005 for Windows, developed by Monolith Productions. Built on the LithTech Jupiter EX engine, it was a technical showcase for dynamic lighting, volumetric effects, and intelligent enemy AI.

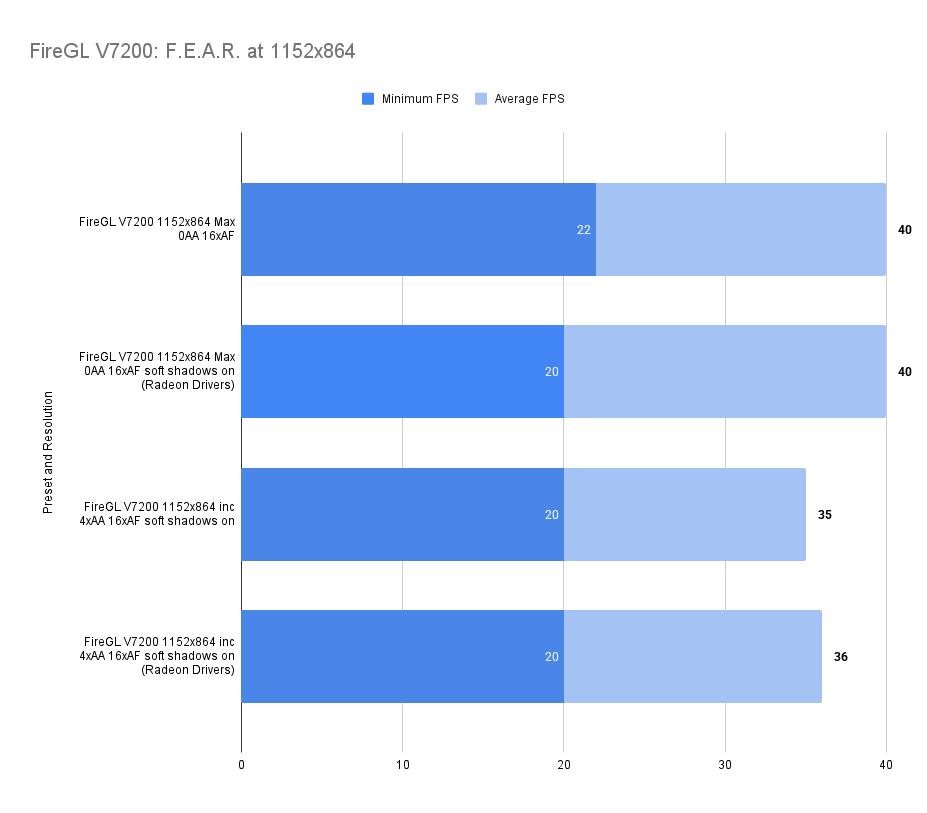

Performance Notes:

Maxed out, the game holds around 40 fps with only a small drop once anti‑aliasing is enabled. It’s a respectable result, though in actual gameplay you’d probably be tempted to dial a few settings back for a smoother feel.

The Radeon drivers produced comparable numbers. Since this is an in‑game benchmark, each run is identical, but even so the differences fall well within the margin of error. Nothing meaningful separates the two here.

These results were taken with soft shadows enabled.

Battlefield 2 (2005)

Game Overview:

Battlefield 2 launched on June 21, 2005, developed by DICE and published by EA. It was a major evolution for the franchise, introducing modern warfare, class-based combat, and large-scale multiplayer battles with up to 64 players. Built on the Refractor 2 engine, it featured dynamic lighting, physics-based ragdolls, and destructible environments that pushed mid-2000s hardware.

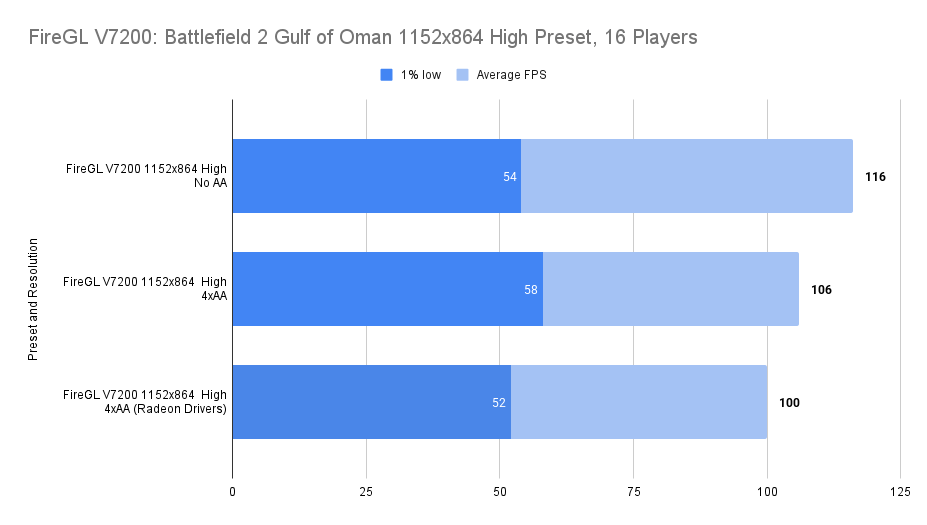

Performance Notes:

For a game released in the same year as the card itself, the results are outstanding. We’re still seeing triple‑digit frame rates, and even cranking up anti‑aliasing barely makes a dent. It’s a fantastic showing and exactly what you’d hope for from hardware of this calibre.

Need for Speed: Carbon (2006)

Game Overview:

Need for Speed: Carbon hit the streets on October 30, 2006, developed by EA Black Box and published by Electronic Arts. As a direct sequel to Most Wanted, it shifted the franchise into nighttime racing and canyon duels, introducing crew mechanics and territory control. Built on the same engine as its predecessor but enhanced for dynamic lighting and particle effects, Carbon pushed mid-2000s GPUs with dense urban environments, motion blur, and aggressive post-processing.

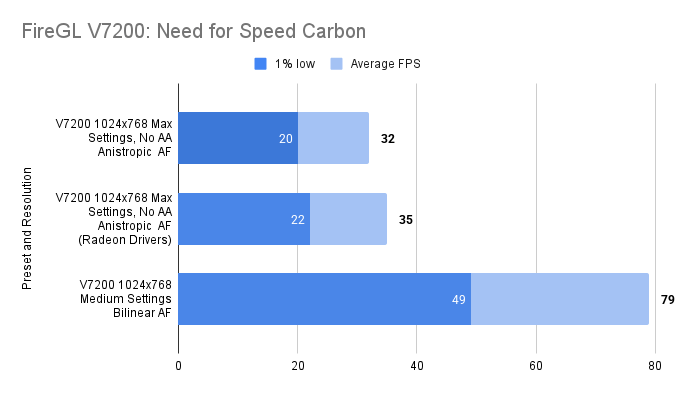

Performance Notes:

At last we’ve found the limit, which is a bit of a shame, but these mid‑2000s Need for Speed titles have always had a reputation for running poorly. In earlier GPU testing, NFS: Most Wanted performed even worse, and although this game uses the same engine, it’s at least a little better optimised.

With everything maxed out, performance drops enough that you’ll probably want to turn a few settings down. Medium settings give a much smoother experience, but it still feels like a compromise considering how well the card handled everything else.

Medieval II: Total War (2006)

Game Overview:

Released on November 10, 2006, Medieval II: Total War was developed by Creative Assembly and published by Sega. It’s the fourth entry in the Total War series, built on the enhanced Total War engine with support for Shader Model 2.0 and 3.0. The game blends turn-based strategy with real-time battles, set during the High Middle Ages, and includes historical scenarios like Agincourt.

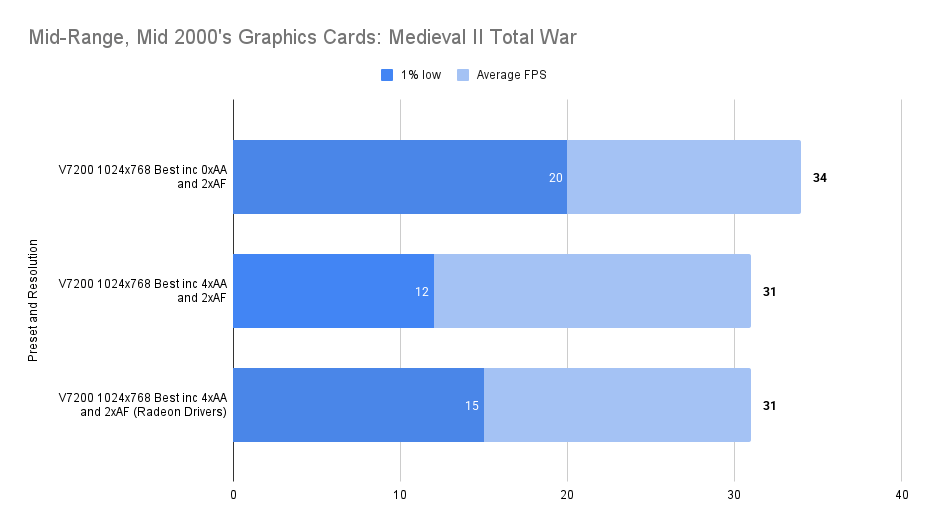

Performance Notes:

I can’t shake the feeling that this game is CPU‑limited, and these results don’t do much to ease that concern. It absolutely hammers a single core, and the old Phenom II chips were never known for strong single‑threaded performance.

Even so, with the best settings we can still squeeze out a somewhat playable frame rate. It’s a long way from the triple‑digit heights we saw in games from 2005 and earlier, but that’s the reality of pairing a mid‑2000s engine with a processor architecture that struggles in exactly this scenario.

Test Drive Unlimited (2006)

Game Overview:

Released on September 5, 2006, Test Drive Unlimited was developed by Eden Games and published by Atari. It marked a major technical leap for the Test Drive franchise, built on the proprietary Twilight Engine, which supported streaming open-world assets, real-time weather, and Shader Model 3.0 effects. The game ran on DirectX 9, with enhanced support for HDR lighting and dynamic shadows, optimized for both PC and seventh-gen consoles.

At launch, TDU was praised for its ambitious scale, vehicle fidelity, and online integration, though some critics noted AI quirks, limited damage modeling, and performance bottlenecks on lower-end rigs. The PC version especially benefited from community mods and unofficial patches that expanded car libraries and improved stability.

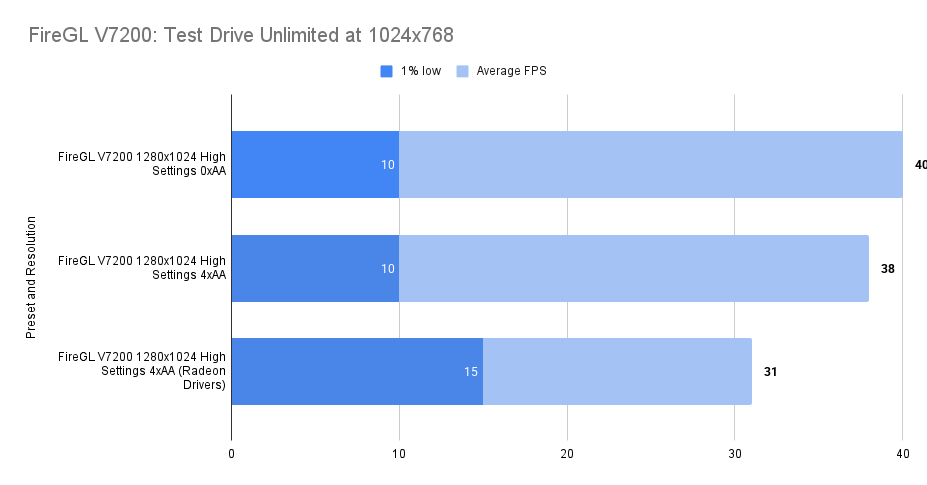

Performance Notes:

A more modern engine really shows where the FireGL starts to struggle. An average of around 40 fps is perfectly serviceable, but the 10 fps 1% low tells the real story — you can feel the stutter, and it’s not subtle.

Interestingly, the Radeon drivers actually improved the 1% low figure, though they pulled the average framerate down at the same time. It’s a trade‑off, and not one that meaningfully changes the experience.

For context, I checked back against the mid‑range cards from 2007. The GeForce 8600 GT managed 61 fps average and 51 fps 1% low, which makes it clear this game strongly prefers unified shaders. The V7200 simply can’t keep pace here.

In the end, it’s a title that really wants more modern architecture. Medium settings or lower are the realistic sweet spot for the V7200.

Oblivion (2006)

Game Overview:

Oblivion launched on March 20, 2006, developed by Bethesda Game Studios. Built on the Gamebryo engine, it introduced a vast open world, dynamic weather, and real-time lighting. The game was a technical leap for RPGs, with detailed environments and extensive mod support that kept it alive well beyond its release window (it’s just had a re-release recently).

Known for its sprawling world Oblivion remains a benchmark title for mid-2000s hardware. The game’s reliance on draw distance and lighting effects makes GPUs struggle.

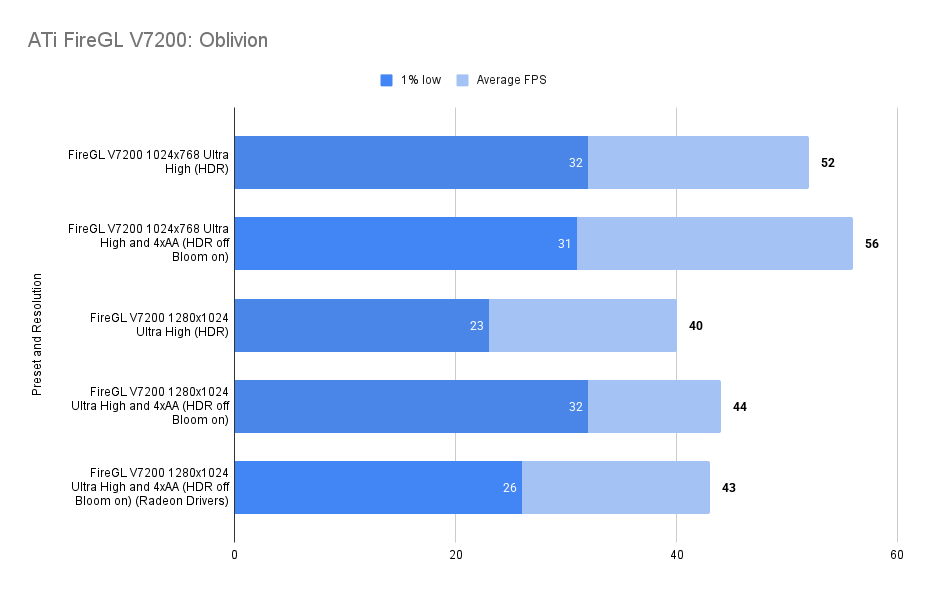

Performance Notes:

I wasn’t ready to give up on the card, so I aimed high again with Oblivion, starting the testing at Ultra settings and the results were surprisingly strong. An average of 44 fps at 1280×1024 with 4× AA is nothing to scoff at for hardware of this era.

The Radeon drivers continued their familiar pattern: broadly comparable, but consistently a touch worse. Nothing dramatic, just enough to reinforce that the FireGL drivers remain the better match for this card.

Crysis (2007)

Game Overview:

Crysis launched in November 2007 and quickly became the go-to benchmark title for PC gamers. Built on CryEngine 2, it pushed hardware to the limit with massive draw distances, dynamic lighting, destructible environments, and full DirectX 10 support.

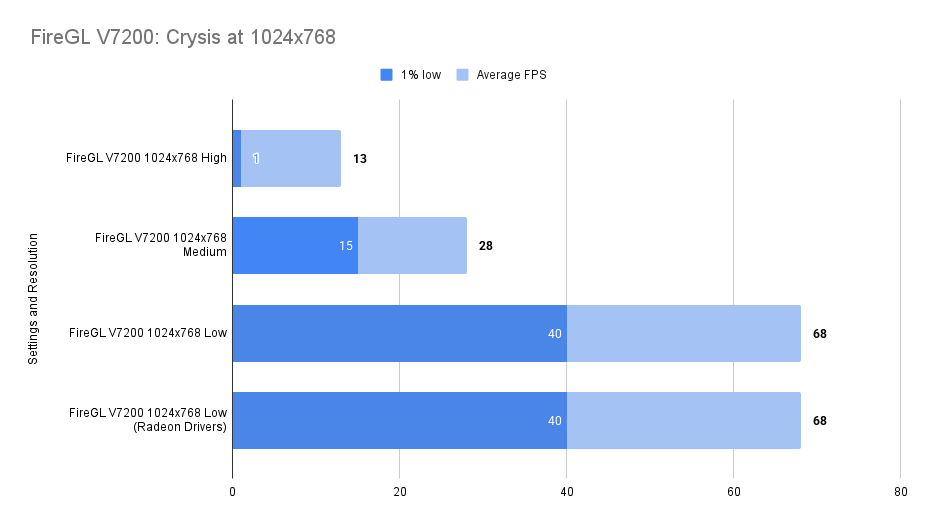

Performance Notes:

An average of 68 fps at 1024×768 isn’t bad at all, even if it requires running on low settings. Medium and high are simply out of reach for this old card — but this is Crysis, so that outcome is hardly surprising.

The Radeon drivers produced essentially identical results in testing, continuing the pattern seen throughout the rest of the benchmarks.

S.T.A.L.K.E.R. (2007)

Game Overview:

Released in March 2007, S.T.A.L.K.E.R.: Shadow of Chernobyl was developed by GSC Game World and runs on the X-Ray engine. It’s a gritty survival shooter set in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, blending open-world exploration with horror elements and tactical combat. The engine supports DirectX 8 and 9, with optional dynamic lighting and physics that can push older hardware to its limits.

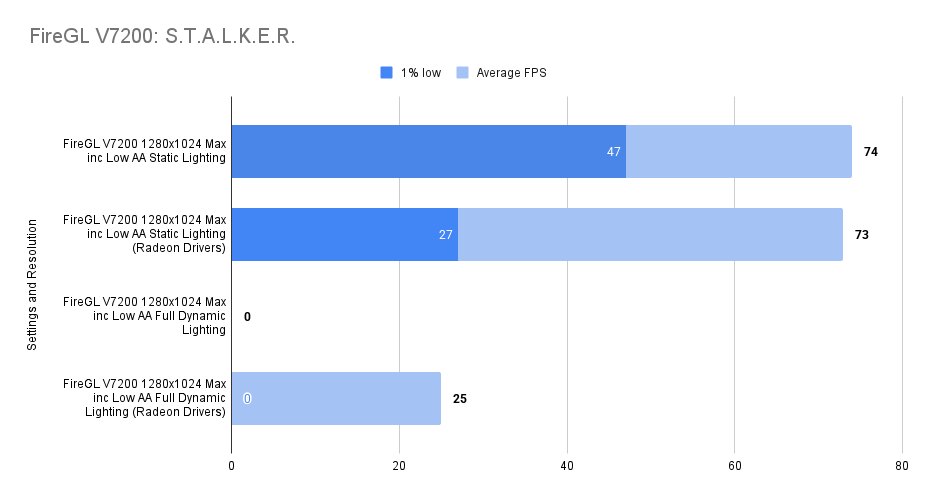

Performance Notes:

With static lighting enabled, the card puts in a very respectable showing. The Radeon drivers land roughly the same average framerate, but with a noticeably worse 1% low, enough to make the FireGL drivers the better choice here.

Getting full dynamic lighting working, however, was a nightmare. On the official FireGL drivers the game would crash outright before a benchmark could even complete. Switching to the Radeon drivers allowed it to get a little further, but the experience was still punctuated by huge pauses every few seconds.

If you want to play S.T.A.L.K.E.R. with dynamic lighting, you’ll need a better graphics card than this one. The difference in behaviour, instant crash versus running with severe stalls, really highlights the diverging driver code paths. The FireGL build seems to hit an unhandled state and bails immediately, while the Catalyst build manages to run but is clearly overwhelmed, likely juggling VRAM aggressively and choking under the workload.

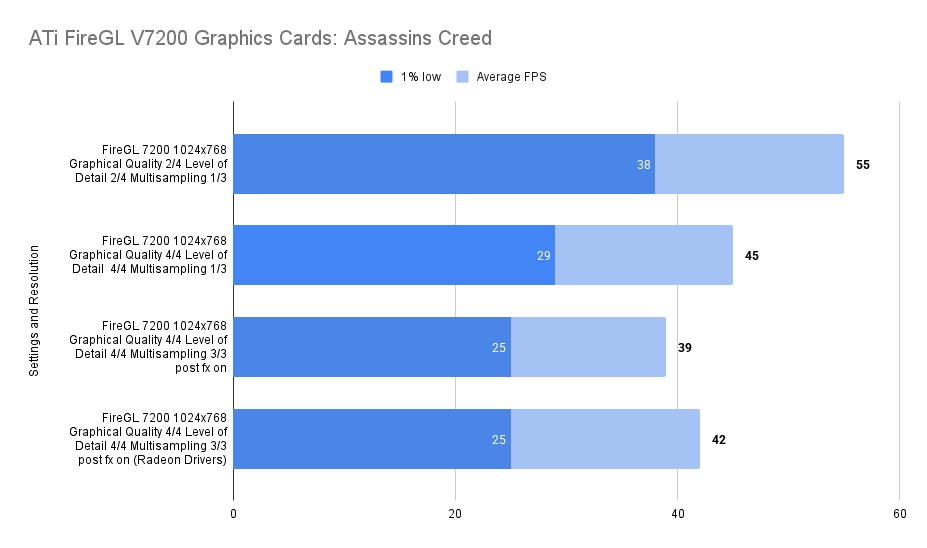

Assassins Creed (2007)

Game Overview:

Assassin’s Creed launched in November 2007, developed by Ubisoft Montreal and built on the Anvil engine. It introduced open-world stealth gameplay, parkour movement, and historical settings wrapped in sci-fi framing. The first entry takes place during the Third Crusade, with cities like Damascus, Acre, and Jerusalem rendered in impressive detail for the time.

Performance Notes:

Jogging through the city in the first Assassin’s Creed and things actually look pretty solid. An average of 55 fps with a 38 fps 1% low feels about as good as this game ever gets at this resolution. So far, on every piece of hardware I’ve tested, this title has never delivered a truly silky‑smooth experience, so this result is right in line with expectations.

Even when pushing the settings to their maximum at 1024×768, performance doesn’t fall off a cliff. The framerate drops, but not dramatically, and the game remains very playable.

At these highest settings, I compared the FireGL and Radeon drivers. The Radeon drivers produced broadly similar results — in fact, they gave a slight bump to the average framerate, though not by any meaningful margin. The overall experience remains essentially the same.

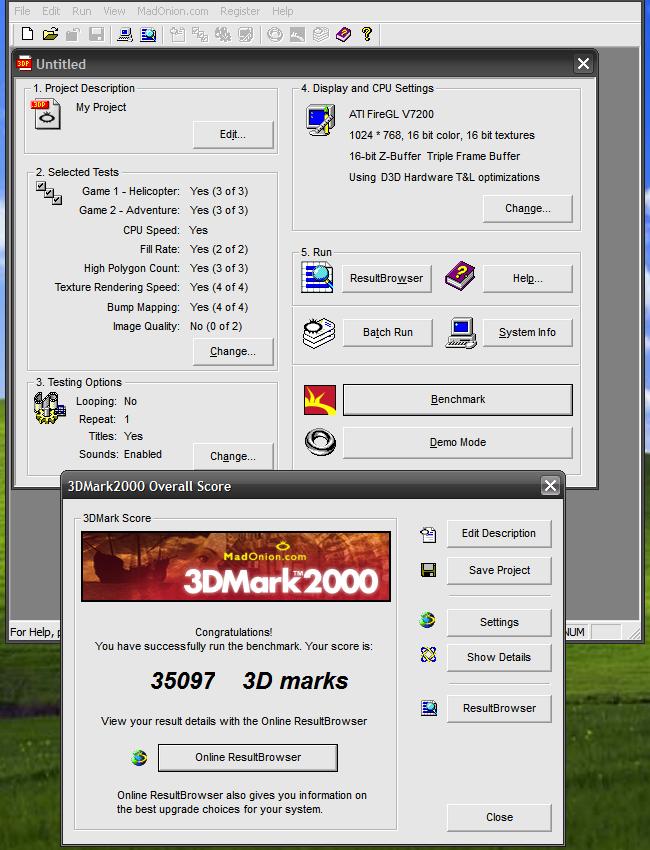

Synthetic Benchmarks

3d Mark 2000

| ATi FireGL V7200 | ATi FireGL V7200 (Radeon Drivers) | |

| Score | 35,097 | 35,226 |

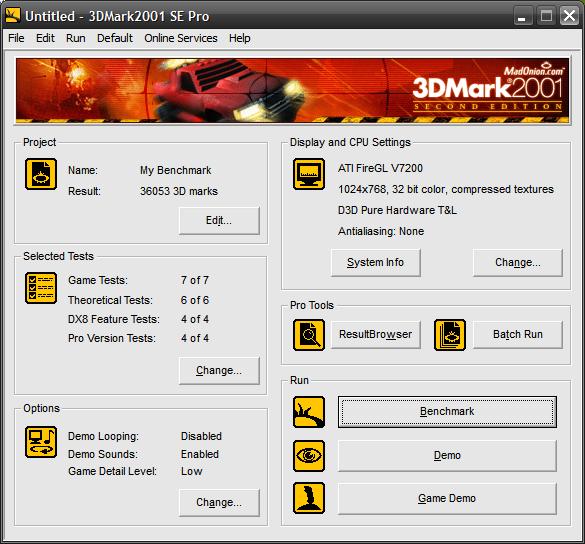

3d Mark 2001 SE

| ATi FireGL V7200 | ATi FireGL V7200 (Radeon Drivers) | |

| Score | 36,053 | 35,998 |

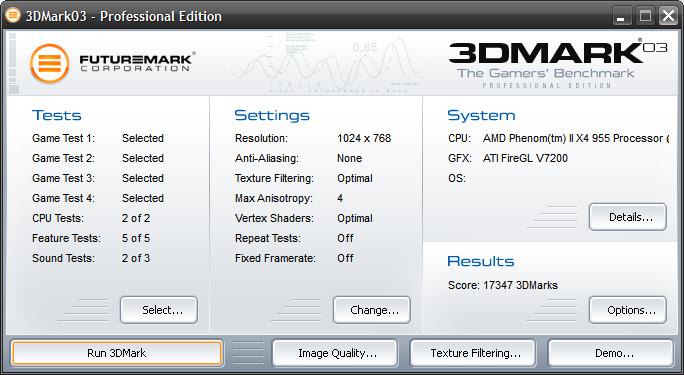

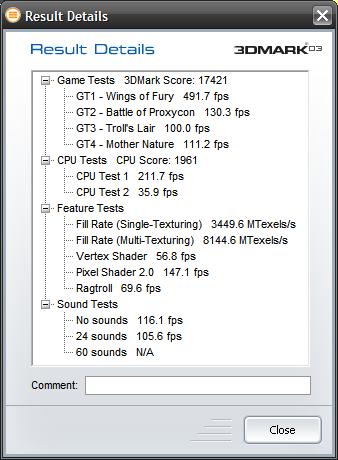

3d Mark 2003

| ATi FireGL V7200 | ATi FireGL V7200 (Radeon Drivers) | |

| Score | 17,347 | 17,421 |

| Fill Rate (Single Texturing) | 3449.6 | 3,449.6 |

| Fill Rate (Multi-Texturing) | 8145.4 | 8,144.6 |

| Pixel Shader 2.0 | 147.1 | 147.1 |

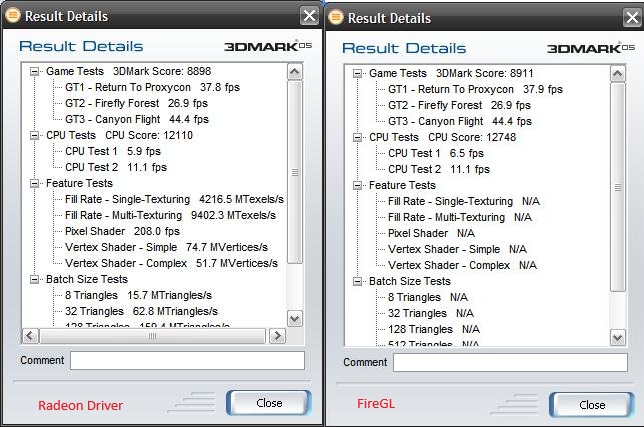

3d Mark 2005

| ATi FireGL V7200 | ATi FireGL V7200 (Radeon Drivers) | |

| Score | 8911 | 8998 |

I did find some online comparisons to the X1800XT:

https://www.cnet.com/reviews/ati-radeon-x1800-xt-512-mb-review/

shows a score for the X1800XT 512Mb version at 9,240 at the same resolution in this benchmark.

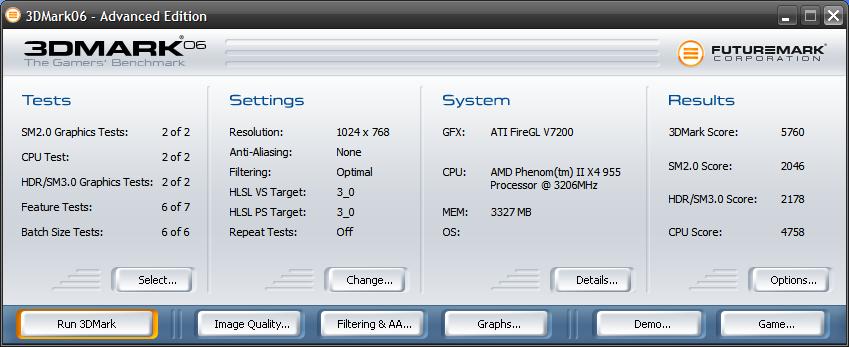

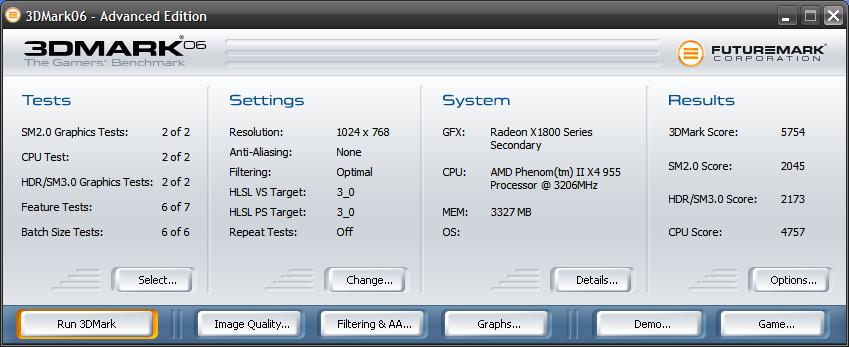

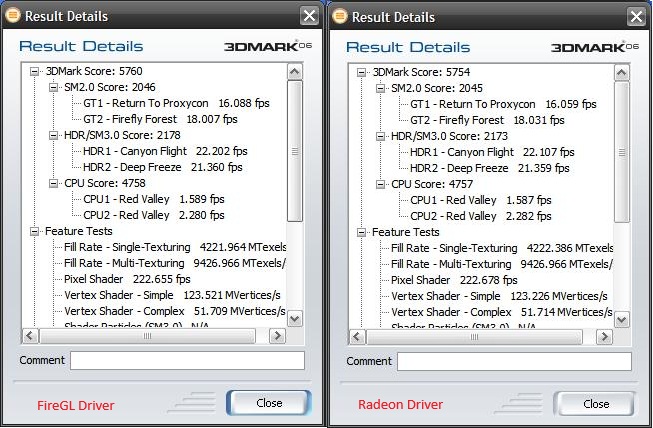

3d Mark 2006

| ATi FireGL V7200 | ATi FireGL V7200 (Radeon Drivers) | |

| Score | 5,760 | 5,754 |

| Shader Model 2.0 Score | 2,046 | 2,045 |

| HDR/Shader Model 3.0 Score | 2,178 | 2,173 |

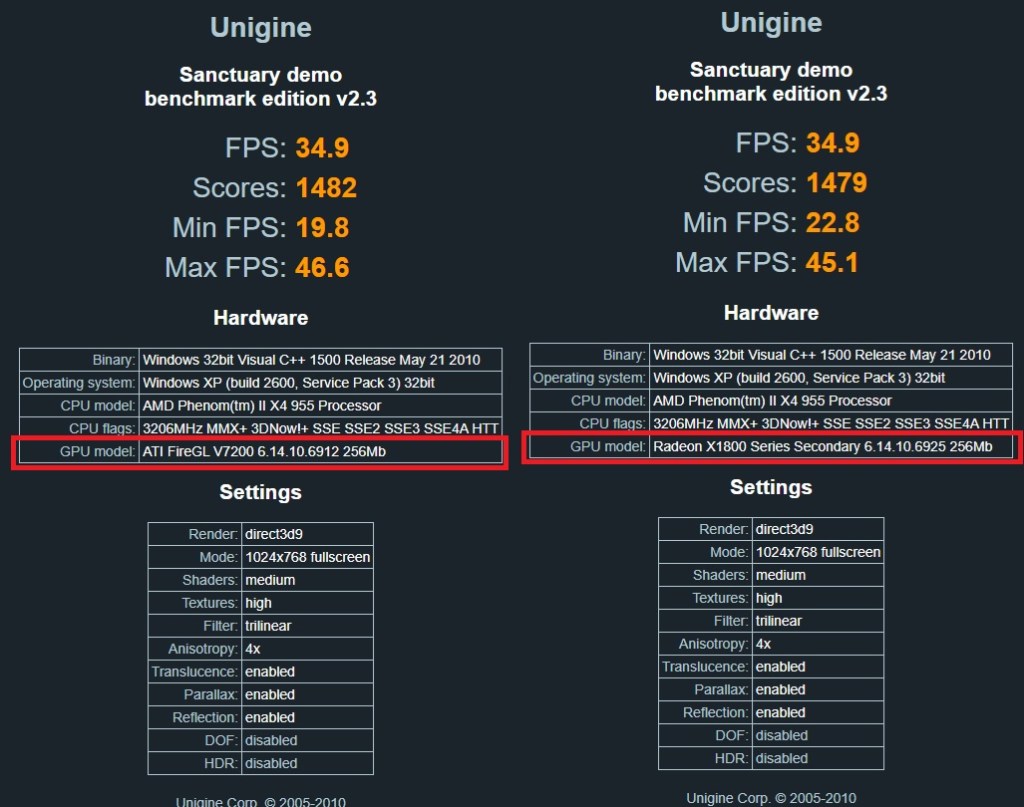

Unigine Haven

| ATi FireGL V7200 | ATi FireGL V7200 (Radeon Drivers) | |

| Score | 1,482 | 1,479 |

| Average FPS | 34.9 | 34.9 |

| Min FPS | 19.8 | 22.8 |

| Max FPS | 46.6 | 45.1 |

Summary and Conclusions

It’s a great card this and I’ve really enjoyed playing about with it, I may just be biased because it looks cool but, when you own as many video cards as I do, it’s good that it stands out.

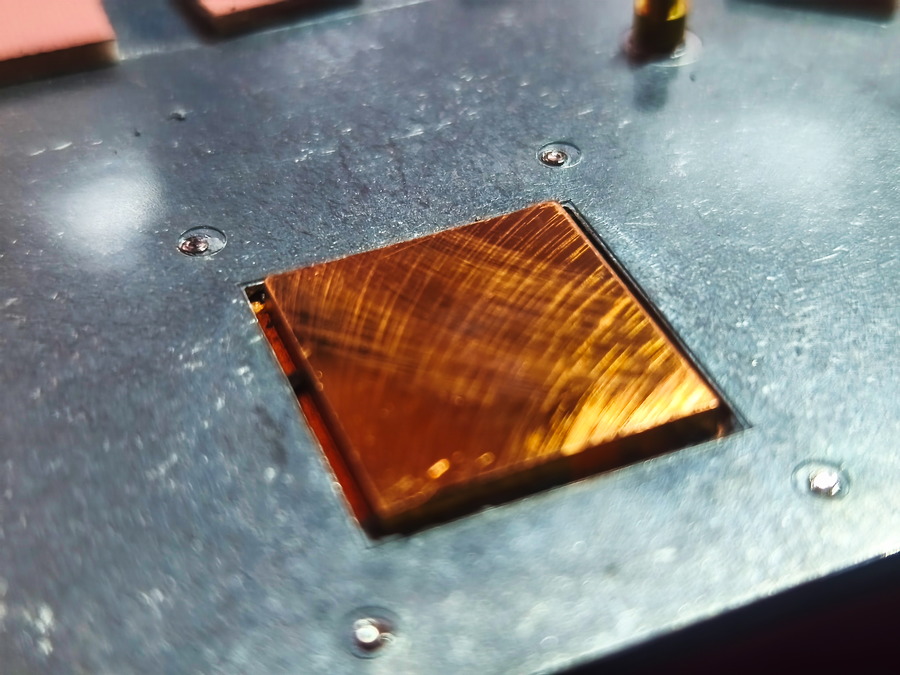

The actual copper being used in the cooling solution shows proper quality.. it does weigh a lot!

Performance wise – it is very impressive, at the time of release, this would play most titles well

Things do seem to fall off a cliff from 2006 onwards, the more advanced features of the new games and tailored towards unified shader GPU’s does the card no favours.

I don’t have much to compare this too yet, but I will put a X1950 pro in there, soon. I’m on the lookout for a good GeForce 7800/ 7900 card which would be great, these don’t seem to be quite so rare, but supply can hardly be called plentiful.

I’m reasonably certain that the FireGL V7200 is every bit as capable as the X1800XT would have been (with a slight handicap due to the slightly lower clock speed).

The drivers seem to make little difference either way and it wasn’t really worth the effort!

As with all articles, I aim to return to this one, perhaps with some more bechmarked games or other testing.

Leave a comment